Faro

On this page:

Faro is the English name for a French card game that developed in the 1600s from the game Basset. It is also known as Pharaoh, Pharo, and Farobank. How it made its way over the Atlantic is unknown, but it was probably English immigrants who brought it with them to the New World. What we do know is that it became a very popular saloon game in North America in the 19th century.

The deck

Faro is played with a standard 52 card deck. There are no jokers. No cards are wild.

Terminology

| Banker | The person handling the bank during a game of Faro. The banker will sell checks (chips) to the players. |

| Punters | The players |

| Checks | Chips (playing markers) |

| Shoe | Dealing box (to place the deck in) |

| Soda | The first card in a shuffled deck. The soda is removed and put aside prior to the first round of Faro. |

| Hock | The last card in the deck. |

Playing Faro

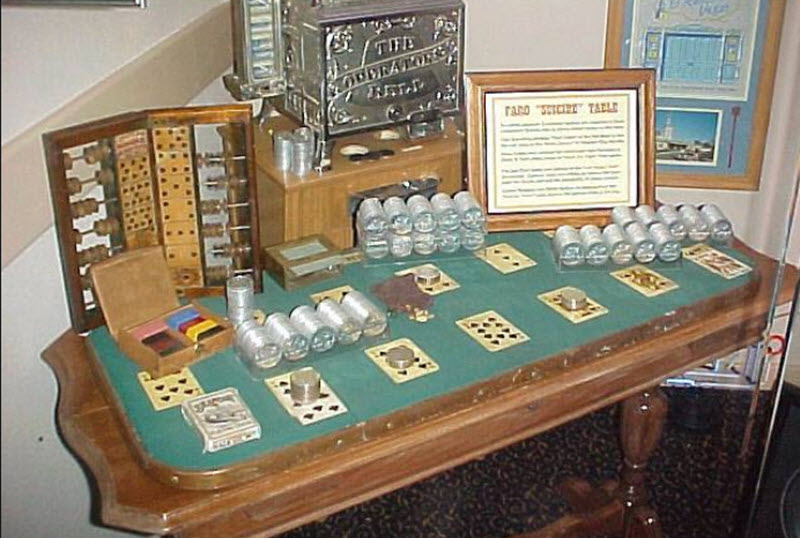

- Faro is traditionally played at an oval table covered in green baize. A board is placed on top of the table and a suit of cards (usually the suit of spades) is placed on the board in numerical order to create a spot for the players to put their bets.

The players place their bets on the suit of cards. If you want to bet on the queen, you put your wager on the queen-card, and so on. You are allowed to put bets on several cards if you want to. You can also split a wager by placing it between cards or on specific card edges in a fashion that you might recognize somewhat from the roulette table.

The players place their bets on the suit of cards. If you want to bet on the queen, you put your wager on the queen-card, and so on. You are allowed to put bets on several cards if you want to. You can also split a wager by placing it between cards or on specific card edges in a fashion that you might recognize somewhat from the roulette table.- An alternative bet called the High Card Bet is possible. The betting area for this bet is located at the top of the layout. If you bet on this, you get paid of the Player’s Card is higher than the Banker’s Card.

- The full 52 card deck is shuffled and placed inside the dealing box.

- The first card (known as the soda) is removed from the deck and put aside. This is known as “burning” and is not unique to Faro.

- The dealer draws two cards. The first card is the Banker’s Card and the second one is the Player’s Card. The Banker’s Card is placed on the right side of the dealing box and the Player’s Card on the left side.

- All bets of the same denomination (regardless of suit) as the Banker’s Card are lost and goes to the bank. All bets of the same denomination (regardless of suit) as the Player’s Card gets paid 1:1 by the bank.A high card bet gets paid if the Player’s Card is higher than the Banker’s Card.

- Bets that haven’t been lost or gotten paid remain on the table unless the punter removes his wager before the dealer draws two new cards.

Special moves and situations

The copper

A punter can reverse the intent of his bet by placing “the copper” on it. This reverses the meaning of the win/loss piles for that bet.

The copper is a six-sided (hexagonal) token. If coppers are unavailable, some gambling halls will use penny coins instead.

Calling the turn

When there are only three cards left in the shoe, the dealer will call the turn. Now, the players can make a special bet by trying to predict the exact order of the three remaining cards.

Then, the dealer will draw the Banker’s Card, the Player’s Card and finally the Hock.

If all three cards are of the same value (which is rare) there will be no calling the turn bet.

The dealer draws a doublet

If the dealer draws a doublet (two cards of the same value), the bank takes half of the stakes upon the card which equals the doublet.

This is the only statistical advantage that the bank has over the player.

History of Faro

During the reign of Louis XIV, a game called pharaon was played in southwestern France. When Basset was banned in France in 1691 Pharaoh emerged as an alternative, but eventually, Pharaoh was banned as well.

In England, both Basset and Pharaoh – known there as Pharo – was widely played in the 1700s. As the game Pharo was introduced to North America, the spelling Faro became dominant. From the mid-1820s and onward, Faro was an extremely popular card game in the saloons and gambling halls in the United States. Data from the civil war period show that Faro was played in over 150 locations in Washington DC alone.

Two slang expressions for the act of playing Faro is “bucking the tiger” and “twisting the tiger’s tail”. In the mid-1800s, the association between Faro and tigers had become so strong in the U.S. that some gambling houses would hang a drawing of a tiger in the window to let gamblers know that Faro was offered inside.

Cheating

Historically, cheating at Faro has been very common and committed by both bankers and punter.

When played without any cheating, the banker (“the house”) has a very low statistical advantage over the punters, causing low long-term profitability for the house. Unscrupulous dealers would cheat in various ways to improve their odds, e.g. by using stacked or rigged decks that would produce plenty of doublets.

One of the most common types of cheating among punters was moving a wager from a losing card to a winning (or at least not losing) card.

Examples of famous faro players

- Giacomo Casanova, a Venetian 18th-century adventurer, and author

- Friedrich Freiherr von der Trenck, an 18th-century Prussian officer

- Casimir Abraham von Schlippenbach, an 18th-century Dutch cavalry commander who, according to his autobiography, won huge sums by playing this game.

- Charles James Fox, an 18th century Whig radical who preferred Faro over all other games.

- Jefferson Randolph “Soapy” Smith II, a crocked Faro dealer and club owner in 19th century Denver, Colorado.

- William “Canada Bill” Jones, a 19th-century scam artist and card sharp in North America

- Whyatt Earp, an Old West gambler, deputy sheriff (in Pima County) and deputy town marshal (in Tombstone, Arizona Territory).

- John “Doc” Holliday, an Old West gambler and dentist who dealt Faro in the Bird Cage Theater in Tombstone, Arizona.

Fictional Faro

- In Leo Tolstoy’s novel “War and Peace”, Nicholas Rostov loses 43,000 rubles to Dolokhov playing Faro.

- Faro is an essential part of Alexander Pushkin’s story “The Queen of Spades”, and consequently also for Tchaikovsky’s opera “The Queen of Spades”.

- In Puccini’s opera “La Fanculla del West”, the miners play Faro in the first act.

- Numerous references to Faro is made in Gunsmoke (both the radio drama and the television series).

- In the video game “Assasin’s Creed Unity”, Arno Dorian plays Faro and loses to a cheating blacksmith.

The players place their bets on the suit of cards. If you want to bet on the queen, you put your wager on the queen-card, and so on. You are allowed to put bets on several cards if you want to. You can also split a wager by placing it between cards or on specific card edges in a fashion that you might recognize somewhat from the roulette table.

The players place their bets on the suit of cards. If you want to bet on the queen, you put your wager on the queen-card, and so on. You are allowed to put bets on several cards if you want to. You can also split a wager by placing it between cards or on specific card edges in a fashion that you might recognize somewhat from the roulette table.